The Swahili language is in the Bantu language family, spoken in central and southern Africa, and it is also heavily influenced by Arabic.

For this reason, there are many aspects that are often challenging for speakers of other languages to learn.

However, Swahili isn’t as difficult as you may think! Here are some of the most common challenges beginners face and how to overcome them.

Table of contents

1. Learning All the Swahili Greetings

There are so many greetings in the Swahili language, and it can be very challenging to learn them all. In fact, you may still come across a new greeting after living in a Swahili-speaking area for years!

Another important fact to know is that unlike in English, if someone says “hello” to you, you can’t just say “hello” back.

In Swahili, sometimes you have one set call and response pair (such as hujambo and sijambo), or multiple options for a response (mambo and the listener’s choice of poa, safi, salama, and more). In addition, jambo, the word most commonly taught to mean “hello,” isn’t actually used as much as you think. Using it can even make you seem like a tourist.

So what should you say instead?

If you are greeting someone casually, mambo goes a long way. It was by far the most common way to greet people in a familiar way that I encountered in Tanzania. When I first arrived and was still an absolute beginner, I made sure I had two possible responses ready to mambo – safi and poa, for example.

Why two? Because a conversation could go like this:

Me: Mambo!

Listener: Poa. Mambo?

Me: Safi.

Although it is natural to repeat the same greeting, it feels somewhat awkward to repeat the same response.

If you are greeting an elder or a boss, stick to shikamoo to show respect. They will always reply with marahaba. Easy!

If you are unsure how casually or respectfully to greet someone, you can stick to habari, which is quite neutral. Like mambo, if someone says habari to you, you can usually use the same responses as mambo.

For more help, be sure to check out our in-depth guide to Swahili greetings so you can have something to say in any situation.

2. Mastering Noun Classes

Swahili doesn’t have noun genders, but it has something called “noun classes” or “word classes.”

This is usually the most difficult aspect of the Swahili language for non-native speakers. Depending on how you count them, linguists say there can be as few as six or as many as eighteen!

But don’t you worry, I have your back.

First, what are noun classes? They are different categories of nouns (such as living beings, natural objects, etc.) that are usually marked with a certain prefix. The core categories for beginners to first learn are as follows with their singular and plural forms:

- M/Wa: For people and animals (ex. mtu “person” and watu “people”)

- M/Mi: For natural objects and body parts (ex. mti “tree” and miti “trees”)

- Ki/Vi: For languages, tools, and man-made objects (ex. kisu “knife” and visu “knives”)

- Ji/Ma: For fruits, natural objects, uncountable nouns (with no singular form), and other miscellaneous nouns (ex. jiwe “rock” and mawe “rocks” / chungwa “orange” and machungwa “oranges”)

- N: For loanwords from other languages and miscellaneous nouns (ex. simu “cell phone” / ndege “bird” or “airplane”)

- U: For uncountable nouns (with no plural form), abstract ideas, country names, and miscellaneous nouns (ex. unga “flour” / ubaya “badness”)

As you can see, some categories are focused, and some are quite broad. A lot of words also don’t fit nicely into these category types. You will pick them up as you learn more vocabulary!

Making Sentences with Matching Noun Classes

In Swahili, adjectives and verbs must match the noun class. For example, a M/Wa noun has the corresponding verb prefix a- (singular) or wa- (plural). The corresponding adjective prefixes are simple: m- and wa-. Therefore, to say “A nice person reads,” you would say:

Mtu mzuri anasoma.

(Person + nice + reads.)

However, to say “Nice people read,” you would say:

Watu wazuri wanasoma.

(People + nice + read.)

Similar to European genders, learning Swahili noun classes requires some patience. I recommend you first find a good textbook or teacher to guide you through them gradually.

You should understand the general categories and make sure to memorize the class whenever you learn a new noun, but don’t try to master them all at once! It takes time, but since they are integral to Swahili sentences, you will figure them out with practice.

I’ll leave an initial resource for you here: noun classes.

3. Differentiating Between Similar Words

Here’s one good news for you: learning Swahili noun classes can help you differentiate between similar words. Not only that, but they can also help you understand the etymology of words and build your vocabulary easily!

How about a few examples?

- “Person” is mtu, but to make the inanimate word “thing,” you just change the noun class prefix to kitu.

- You can see above chungwa is “orange,” so add the natural prefix m to it to get the tree: mchungwa.

- “Meat” is the N class noun “nyama,” and to say “animal,” just add the living being prefix m to make mnyama.

- “England” is Uingereza (U class), and the English language is Kiingereza (Ki/Vi class).

See how all these words are related!

Sometimes, it takes a little bit of creativity to see the connection.

For example, upepo (U class) is “wind,” and pepo / mapepo (Ji/Ma class) is “demon” / “demons.” They might not seem intuitively connected at first, but remember the native religions in East Africa were often animistic and believed in spirits in the natural world.

Maybe it was a demon that caused the wind!

Expert note: There are other similar-sounding words unrelated to word class that you will need to be careful to learn properly. Two sets of verbs that I always thought through before I spoke were kuelewa (“to understand”) and kulewa (“to be drunk”), as well as kunywa (“to drink”) and kunya (“to poop”).

But… Mixing these up as a beginner is fine! It will even make for funny stories to tell your friends. Again, practice makes perfect.

4. Natives Speaking Too Quickly

Here’s a quite good problem to have: When native Swahili speakers know that you are learning their language, they will be very excited to speak to you in Swahili! From my experience, even if the person I’m talking to speaks fluent English, they’ll jump at the chance to let me practice my Swahili.

This is an amazing opportunity to practice as much as you can!

Feeling intimidated? Oftentimes I found that the people I was conversing with spoke way too quickly and often used vocabulary and grammar far beyond what I had learned. So what should you do?

First, don’t be afraid to let the other know that you’d like them to speak more slowly. You can tell them, Ongea pole pole, tafadhali (“Speak slowly, please”). Or you can ask them to repeat: Sema tena, tafadhali (“Say it again, please”).

Don’t know a word? You can say, Neno hilo linamaana gani? (“What does that word mean?”). If nothing else, tell them that you don’t understand: Sielewi.

Of course, your listening will get better with practice. You can find a good language partner or language tutor to help you improve.

Another of my favorite methods is listening to podcasts, which you can do on your own schedule.

5. Encountering Different Dialects (or Offshoot Languages)

In almost any language you learn, you will come across different dialects. Swahili is no exception.

Since Swahili is a lingua franca of East Africa, it is spoken in many countries. It is an official language and widely spoken in Tanzania and Kenya, and it is also an official language in Uganda and Rwanda. It is a recognized minority language in Burundi, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The language can change somewhat across nations and even within the same country. For example, a minibus in Tanzania is called a daladala, but the same thing is called a matatu in Kenya.

But think about how American English and British English don’t always agree on words: “apartment” and “flat” are widely different, but you’ve learnt that they are both the same thing, haven’t you? The same will happen with Swahili.

Additionally, Swahili spoken in Tanzania and along the Kenyan coasts is thought to be the most original form of Swahili. Some Swahili speakers will characterize it as “pure,” while others will see it as “textbookish.”

In fact, if you go to Nairobi, you will find that many people speak Sheng. Some linguists view Sheng as a Swahili slang dialect, while others view it as a separate pidgin or creole language!

Luckily, Sheng aside, the Swahili dialectal differences are generally not as extreme as other languages, such as Arabic. If you learn standard Swahili, natives from every region should be able to understand you.

Then, once you have a foundation, you can start learning a local dialect (if you so desire!).

6. Old Teaching Resources

Finally, the last thing to watch out for on your Swahili language learning journey is outdated teaching methods and materials.

Some Swahili textbooks still in circulation were written quite long ago. They can use old language or introduce vocabulary that isn’t relevant to modern life. Some Swahili teachers even learned to teach from these resources.

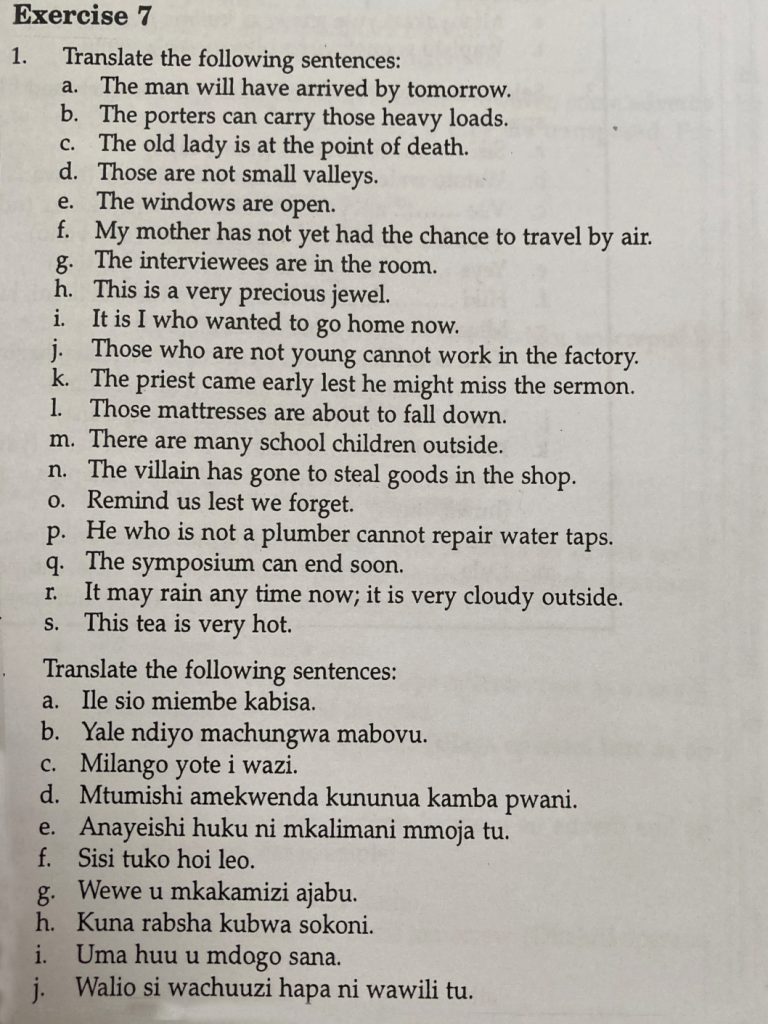

Here is an example of what I mean. When I arrived in Tanzania with almost no Swahili, I joined a beginner group tutoring session. For most of it, we had to translate sentences between Swahili and English. Below is an example of a textbook exercise on which my tutor was basing her lessons:

The book was introducing fundamental grammar (the present tense), but the bulk of the sentences it was asking me to translate were not necessary to my daily life or normal conversations. The only ones I found immediately relevant to me were the very last two in part one!

I was also confused by the old English – would I be sounding like a Victorian too if I used the Swahili it taught me?

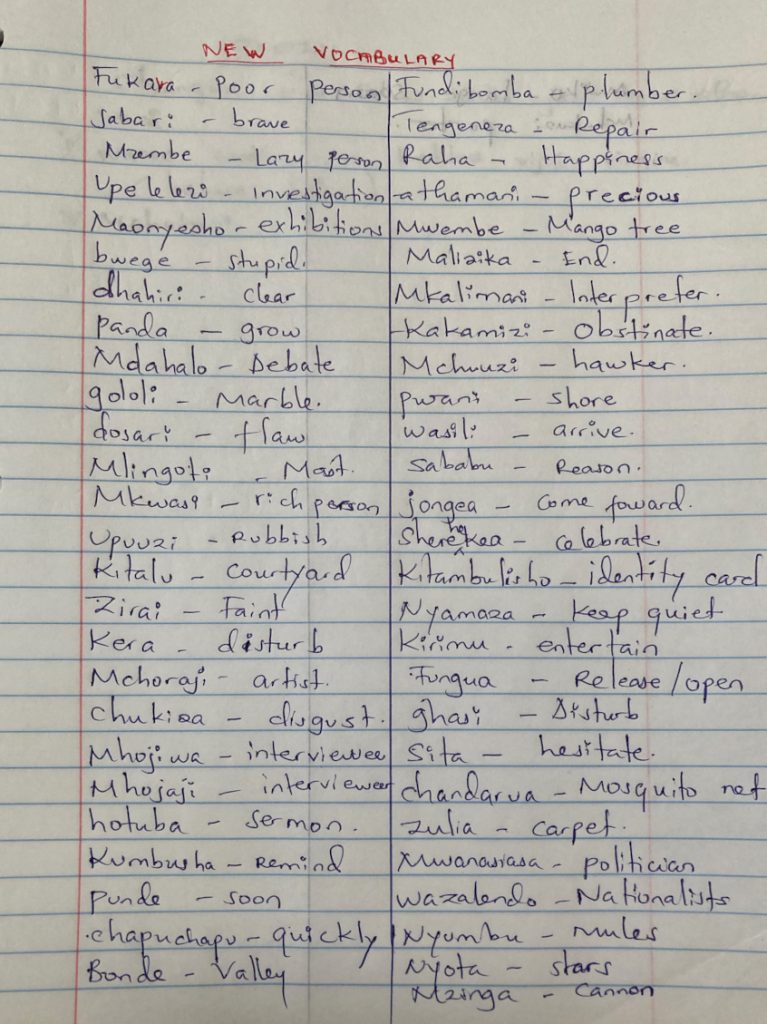

To continue, based on the exercises, the tutor made a list of new vocabulary:

Granted, I appreciated the tutor doing her best to help me get through the exercises, and some of these words were quite useful. Chandarua (“mosquito net”) was a very important item to have, and at night, I often went to look at the nyota (“stars”). However, as far inland as I was, there was no reason for me to talk about a ship’s “mast” – or “cannons,” for that matter.

I also later learned that some of these words were a bit formal and not used as often as colloquial counterparts – and this was for both Swahili and English. I didn’t study hotuba at first because I don’t often talk about “sermons,” but it became an important word when I later learned it also means “speech”!

From my experience, many Swahili teachers and tutors learned how to teach through older methods, such as the grammar-translation method above. This may not be suitable for your needs. Now, I’m not saying that the grammar-translation method isn’t useful – I personally believe that it still has a place in language learning.

As long as the phrases and sentences are relevant to your life, it is one useful way to learn languages. However, nowadays there are many alternatives to this classical method to use instead of or in combination with grammar and translation study.

So what should you do? If you choose to use a tutor, make sure you communicate what you want to learn or practice with them early on.

Be clear and transparent with them – if something isn’t working for you, feel free to communicate so in a polite manner. Usually your tutor will be very happy to understand your needs and style better!

Even if they learned through classical methods, many would welcome a chance to try different methods so they can develop their teaching skills further. If it’s just not a good match, you can always try another.

Likewise, shop around for a textbook or learning material that suits you best. I personally found Complete Swahili (formerly known as Teach Yourself Swahili) to be a very reliable and well-rounded textbook.

I particularly liked that it has language lessons and cultural notes geared toward a variety of contexts, whether you are in a Tanzanian city or a Kenyan coastal village.

The Swahili Language Isn’t That Hard!

The Swahili language has some difficult aspects, but of course, there will be difficult aspects in any language you learn.

Luckily, once you get past these challenges, the rest of the language is quite easy!

So go ahead – read, write, speak, and listen to Swahili, and you’ll master even the most difficult parts of it in no time.

The post Is the Swahili Language Hard to Learn? 6 Common Challenges and How to Overcome Them appeared first on Fluent in 3 Months.

0 Commentaires